It's served to us in many different styles - some more palatable than others - but we can’t deny the surge of historical interest in food taking place over the past few years. Drawing on various forms of expertise, food history seems to be one of the few topics to connect the world of investigative journalism to the ivory towers of academia. We would expect that historians, perhaps, would gravitate towards broad processes –– such as the spread of industrialization

that gave birth to the grocery store and the tin can, or the culinary impact of

immigration and the rise of ‘counter-cuisine.’ We might expect journalists, on

the other hand, to unmask more immediate concerns, such as the arduous journey

from farm-to-table or the politics of GMO labeling, compelling us to think

twice about what we select from our grocery store shelves.

But maybe our interests are more alike than

we think. The last two food history

books I have read have grappled with several ancient yet still exigent issues in food

history worthy of further exploration. The

first one, historian Dr. Emma Spary’s Eating the Enlightenment: Food and the Sciences in Paris 1670-1760 (University of Chicago Press, 2012) examines

the animated debates about alimentary knowledge during the 18th

century, ranging from the physiology of digestion to the chemistry of alcohol

distillation. The book is written with a

specialist audience in mind: rewarding reading provided one reads with a pen in hand. The second, Pulitzer

Prize winning journalist Michael Moss’s

Salt: Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (Random House, 2013), examines the understudied

phenomenon of modern processed food and the political machinations of the

industries that design and sell it. The

reading is as addicting as the Cheetos and Twinkies that he describes. I picked these books up for very different

reasons, but both, I think, raise important questions about our understandings

of taste preferences, addiction, and the relationship between food and

drug.

1) Matters of

Taste

Straddling self-preservation and leisure, philosophers and

physicians have long considered taste to be the most enigmatic sense. The Roman Epicurean poet Lucretius posed the

question in the first century B.C.

|

| Lucretius, Roman poet and Epicurean |

“Now, how it is we see

some food for some,

Others for others …

I will unfold, or

wheretofore what to some

Is foul and bitter,

yet the same to others

Can seem delectable to

eat?”

Drawing on the works of eminent French physicians and cooks,

Spary examines the heated debates ignited by the rich, delectable flavors of fashionable

nouvelle cuisine. As culinary masterminds attempted to dazzle

the palate with seasoned ragouts and fricassees, they also marketed gustatory enjoyment

of them as a social virtue. Over the

first half of the 18th century, she argues, physicians anatomically

linked a delicate palate attuned to culinary artistry and subtle flavors to a

lucid and productive mind.

Spary’s physicians are essentially the ancestors of the food

scientists today working at the Monell Chemical Senses Center, where the manufacture

of gustatory delight is now a multi-billion dollar industry. Moss invites us into this Wonka-like behemoth in Philadelphia, where chemists tinker with smell,

taste, texture, and aesthetic appeal to design the cookie or soft-drink guaranteed

to bring in the biggest profits. I was

particularly struck by the fact that heavy loads of salt, sugar, and fat do equally great wonders for texture as much as taste, making Wonder-Bread puffy, Cheetos crispy,

and Lunchables chewy. Indeed, seems like the processed food

industry has whittled our flavor preferences down to a science. “People like a chip that snaps

with about four pounds of pressure per square inch, no more or less,” one food

scientist matter-of-factly reports, leaving me wondering whether the

subjectivity of human taste preferences celebrates the individual as we like to think.

2) Nourishing Bad

Habits

Likewise, the relationship between taste and habit formation is

hardly new. The famous 17th

century physician Thomas Willis described the pleasure of eating tasty foods as

a God-given reward for the monotonous

and laborious act of eating necessary to keeping us, and the human race, alive. (The same logic was also used to explain the

pleasure of sex.)

|

| In his theory of two souls, Thomas Willis (1621-1675) speculated why food tastes good |

Our understandings of

habituation and addiction are quite different today. As eating was necessary to human

survival yet was also subject to the spontaneous grumblings of the stomach,

“alimentary pleasure” Spary observes, “occupied a grey zone of permissible

indulgence.” So long as he could sublimate his appetite to his faculty of

reason, the 18th century enlightened eater was permitted to enjoy

the delights of haute cuisine. But not

everyone was capable of handling these gustatory pleasures. The aspirational parvenu and the coarse

country brute, unsurprisingly, were most at risk of getting carried away. The 18th century science of

addiction, Spary explains, therefore had little to do with the chemical

composition of tasty foods themselves, but was enmeshed in the ideas of luxury,

decadence, and indulgence that eating these foods presupposed.

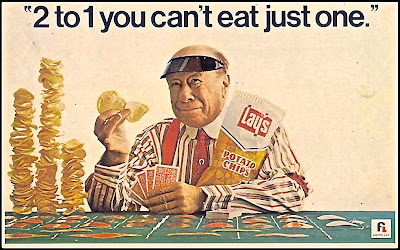

The delicate 18th century ragout thus bore a striking resemblance to the taunting motto

emblazoned on every bag of Lay’s potato chips: Betcha Can’t Eat Just One.

Moss, however, is less interested in the social forces informing the

production of physiological knowledge, proudly standing by his oh-easy-to-hate

culprits: salt, sugar, and fat. It is the

expert manipulation of these substances that induce people to inhale a bag of

potato chips in one sitting and to (falsely) believe that their waistlines can

get away with it. I found Moss more

compelling when he discusses the disingenuous tactics by which corporations

have hooked populations on processed foods.

Virtually all of the food scientists he interviews –– the engineers of

everything from Dr. Pepper to Lunchables –– do not dare touch the food that

their employers unscrupulously market to our society’s most impoverished and

vulnerable demographics. When it comes

to our habituation and addiction to the “wrong” foods, the forces of social

distinction always seem to be at work.

|

| Are the processed food industries mocking our lack of willpower? |

3) Food and

Medicine

Last, Spary and Moss both explore the relationship between food

and medicine. These distinctions are also

thousands of years old. In the 4th

century B.C., Hippocrates exhorted us that every doctor should also be a good cook, as pleasant tasting

food was easier to digest than nutritionally identical food that was perhaps

less pleasing to the palate. (Ayurveda

and many other forms of alternative medicine are gaining interest in the West because they operate according to a similar logic, discussed in a previous post. Spary

shows us how the medical categories assigned to food –– whether they are

“addictive” or “healthy,” “nourishing,” or even counted as food at all –– are

highly unstable and are constantly evolving.

While today’s food scientists might balk at classifying coffee and

liquor in one alimentary category, 18th century chemists believed

the essential salts in both substances shared certain healthful medical

properties –– “spiritual gasoline” –– that affected the brain and nerves in

ways more alike than different. Nutritional beliefs are shaped by far more

than science alone, but also incorporate political, social, and cultural

factors.

|

| Tang Advertisement, c. 1960 |

But does this apply to Tang and potato chips? It might be hard to believe that processed food had ever been

touted for its medical properties, but Moss warns us not to forget that the

1950’s “Golden Age” of food processing once signified the triumph of American

progress and ingenuity. Tang, for

example, fortified with nutrients, was considered an effective and tasty

solution to the high cost and limited accessibility to regular orange juice. Today, however, the gurus of food processing

are singing a different tune, as Moss learns during his trip to Nestlé’s

research center in Switzerland. Here, food scientists keep busy testing potential state-of-the-art alimentary solutions to the obesity problem.

The nature of their research, unfortunately, suggests that it

might be too late. We hear about new products

like “Peptamen” ingested through a tube to feed the alarming numbers of men,

women, and children that have undergone gastric bypass surgery to shrink their

stomachs yet still can’t rein in

their cravings for nutritionally devoid processed food. Indeed, the new ‘science’ of medical nutrition

seems to be suggesting that maintaining health and losing weight the

old-fashioned way –– by eating –– might be a relic of a by-gone era. This might be more serious than a

capitulation to the obesity epidemic, bad as that sounds. These new products suggest that the

distinctions between food and medicine, which part ways during the 17th

century, might now, in the 21st century, be drawing back

together.

I picked up both of these books for very different reasons, and

I enjoyed both of them tremendously, albeit in different ways. Despite the differences in subject matter and

approach, both of these books illuminate the messy political, social, and

intellectual forces that inform our knowledge of food. There is nothing inevitable, both books

conclude, about the ways whereby our food decisions take shape. But both of these books open new questions

about our relationship to food –– about consumption, about agency, about the

politics of alimentary knowledge –– that show us that there is far more

research to be done.