In 1709, the famous London journalist, Edward "Ned" Ward, discusses a so-called “Vertuoso’s Club,” composed of Royal Society members who met at a London tavern every Thursday. On one of these weekly meetings, a member brought an “Aegyptian Cargo of stinking Suppositories” and proceeded to list the miraculous medicinal effects of this exotic drug. As cultivated gentlemen are wont to do, he duly passed free samples around to all of his fellow members.

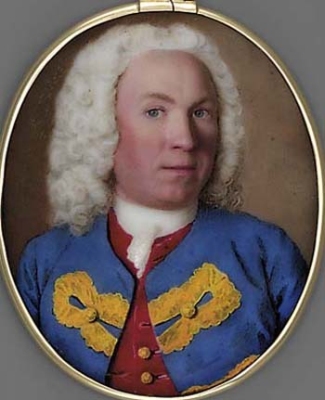

| Ned Ward, London Lowlife |

Ned Ward reports:

“... every one nibbling at the sharp-end that had lain stewing in the Dregs, some nodding their Heads, as if they had found by the Taste, what Analogy it had with some other Species that was noted for its Vertue. Others spitting out what they had chew’d and mumbl’d, for fear the Secret should produce some poysonous effect. One declaring, it must be a great Dryer, because of the Spiciness of its Taste. Another, That it was certainly a powerful Antiscorbutick, because so full of Saline Particles. A Third, That he believ’d it was Antivenereal, because its biting Taste had some affinity with Guaicum. A Fourth, Asserting it a great Narcotique, for that it had numb’d his Tongue, by conveying it to his Palate. Thus the Jest went round, till every Member of the Club, who had the least skill in Physick, had most gravely deliver’d his Judgmatical Opinion."

In 1709 (over 30 years before the Thursday's Club was officially founded) the subjective nature of the sense of taste plagued even the most educated minds. Every Club member tastes the same substance and uses his powers of the palate to situate the mystery substance into the existing body of medical knowledge: what it is, what does it do, how it is classified. Yet every observation is different; everyone finds something peculiarly noteworthy about what he is tasting.

|

| The Italian scientist Marcello Malpighi's drawings of the tongue |

Beginning in the 1650s and 1660s, scientists all over Europe began to investigate the sense of taste. They studied the anatomy of the tongue, they tinkered with wine, beer and cider making, and they argued relentlessly about how many different flavors existed. But they couldn't really get anywhere. Why does what tastes salty to you taste sour to me? Why do you like Madeira wine, but I prefer Claret? Determined to find an answer, scientists eagerly whipped out their microscopes (which had only recently been invented) and tried to explain the unexplainable from their visual observations of salt and sugar particles (combined with taste tests, of course).

But the joke was on them, as Ned Ward reveals in his story. The club members gradually learn that the natives didn't ... well... they didn't actually eat the drug that had baffled their palates. No indeed, it was intended for another bodily orifice altogether. And these suppositories that the members were churning around in their mouths? Yep. They had all been used before.

Needless to say, the "Vertuosos," after spitting and puking and yelling obscenities, saw this act as grounds for club expulsion.

But what is Ward trying to tell us about taste? Is he simply exasperated with the scientific elitism? Or is he making fun of the emerging culture of connoisseurship that was popping up in fancy French taverns and coffee-houses all over London?