|

| "An Oyster-Seller," from Cries of London Paul Sandby, 1759 (Recently viewed by this blogger in the London Museum) |

Servants also had access to fine food, and it has already been observed that, since they often got to dine on their masters’ leftovers, they generally ate far better than others of their station. But did they adopt their masters' tastes?

Let's see what some of the literary big-shots have to say. Daniel Defoe loved to complain about the low quality of service in those days. So just for fun, I searched all of his anti-servant rants for the Dickensian keywords for the idle poor: “venison” “turtle soup” “gold spoon.” Nada. Defoe seemed more inclined to think that servants preferred to steal their masters’ fine food and sell it for a profit.

|

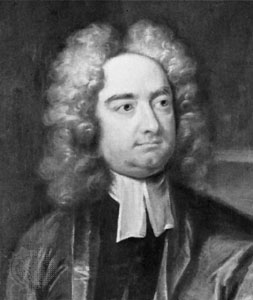

| J. Swift |

What about Jonathan Swift? In Directions to Servants, (1731) his semi-absurd guide to cheating, extorting, and generally creating health-hazards for masters throughout Britain, I've extracted the following tidbits:

"To save time and trouble, cut your apples and onions with the same knife, for the well-bred gentry love the taste of an onion in every thing they eat."

and

"Place birds in the dripping pan, where the fat of roasted mutton or beef falling on the birds, will serve to baste them ... for what cook of any spirit would lose her time in picking larks, wheat-ears, and other small birds?"

But nowhere does he actually promote eating the masters’ food. Rather, he is most likely to advise extorting them by mixing foods together that are meant to be separate. This kind of misbehavior is satirically purported to give dishes a “high” or “French” taste, as if onion and oil in everything is all too often mistaken for the flavor of money and sophistication.

So maybe published sources aren't the best way to go on this one. But what do the archives tell us?

That's coming up next.

No comments:

Post a Comment